By Brett Zupan

One of my greatest pleasures of working at Gate 15 is that we get to dig deep into the security issues our clients face. Our company’s threat-informed, risk-based approach allows me to interact with the root causes of the concerns American leaders and businesses have to confront during their day-to-day operations. So it’s likely no surprise that, when it came to serving my community in 2021, I used our annual service week to delve into our nation’s history and contribute to the preservation of the records that show the path our country has taken.

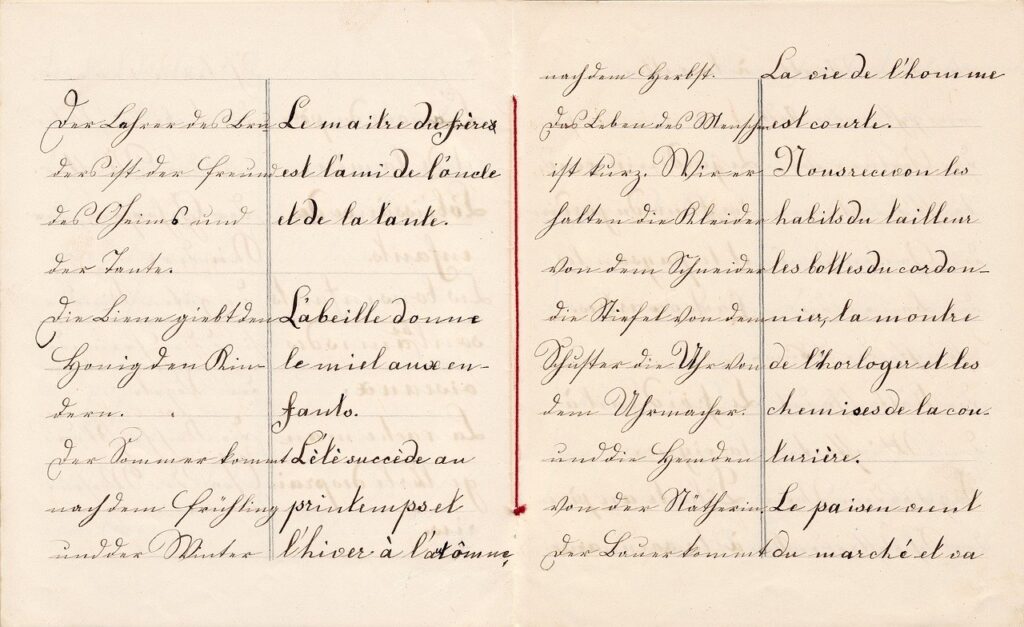

The Smithsonian Transcription Center is what gave me this opportunity. As an online portal for crowdsourcing the digitization of the Smithsonian’s collected papers, the Transcription Center provides a platform for Smithsonian institutions to release scanned copies of their materials for volunteers to translate into electronic documents. The portal is a one stop shop for anyone to view scans, input transcription, and review others’ efforts.

The remote aspect of volunteering for the Smithsonian Transcription Center was especially attractive to me due to the COVID environment we’ve all experienced for the last two years. The Center allowed me to substantively contribute without exposing myself to risk in a group environment, though the center does promote in-person “Transcribe-a-Thons” where volunteers are able to meet up and work together to focus on specific projects.

While there were projects from a variety of institutions available, I decided to focus on the Freedmen’s Bureau project. The goal of this collaboration between the Transcription Center and the National Museum of African American History and Culture is to make 1.5 million pages of records from the Freedmen’s Bureau available publicly online and searchable. In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, the Freedman’s Bureau was responsible for aiding formerly enslaved Americans in their transition to freedom. This aid included providing necessities, arranging legal aid, and settling freedmen on abandoned lands. However, the Bureau did not weather political opposition from the president and shut down after only 7 years.

Transcribing the documents was rather meditative, considering how mentally intensive our work can usually be. I mainly focused on records regarding distributed food packets and indenture contracts, kept track on the county level by the Bureau’s agents. Even through the numbers, I got glimpses of the lives of the people the Bureau touched, in small comments on the side of entries or in the names of repeat customers.

The indentured records were especially impactful since all of the contracts listed were for children 18 years or less. Seeing their names, ages, and the agents’ comments about their parents made them real to me in a way I didn’t expect. I did personal research on the amount of money businessmen paid to the children’s’ families for their time as indentured workers, trying to understand how common these arrangements were and who they benefited the most. I am not a historical scholar, but the research I did helped me understand that, for all the importance of the Civil War to the freeing of slaves, the immediate aftermath of the conflict had a much greater impact than we are taught on how much this freedom was made real on the ground.

Overall, I enjoyed my time volunteering for the Smithsonian Transcription Center. It was a safe, relaxing, impactful, and enlightening experience. I would definitely recommend virtual document transcription to anyone that still wants to contribute to history and scholarship during this era of the COVID pandemic. Gate 15 gave me the opportunity to do just that, and I am grateful to have served the Smithsonian community in this small way.