The National Terrorism Advisory System is an inadequate tool to communicate threats and risks to homeland security.

From Friday, over the weekend, and continuing, organizations around the world, to include numerous entities within the critical  infrastructure community, have been racing to protect themselves against the WannaCry ransomware outbreak that has impacted organizations worldwide. There is abundant information on that available; the threat itself is not the focus of this post. But, if you’re still trying to wrap your head around what this is all about, here are some quick links that could be useful:

infrastructure community, have been racing to protect themselves against the WannaCry ransomware outbreak that has impacted organizations worldwide. There is abundant information on that available; the threat itself is not the focus of this post. But, if you’re still trying to wrap your head around what this is all about, here are some quick links that could be useful:

- Recorded Future: What Is WannaCry? Analyzing the Global Ransomware Attack;

- Troy Hunt: Everything You Need to Know About the WannaCry / Wcry / WannaCrypt Ransomware;

- F-Secure: WCry: Knowns And Unknowns;

- Or scan the Gate 15 Twitter feed for a long list of references and updates (and follow us and scan it daily!)

Cybersecurity firms, researchers, and information sharing communities have been working relentlessly to understand, educate, and protect organizations against this threat. The US Department of Homeland Security (DHS), to its credit, has been working with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to provide updates and share information on this threat. And on Friday, DHS released a statement regarding the attacks.

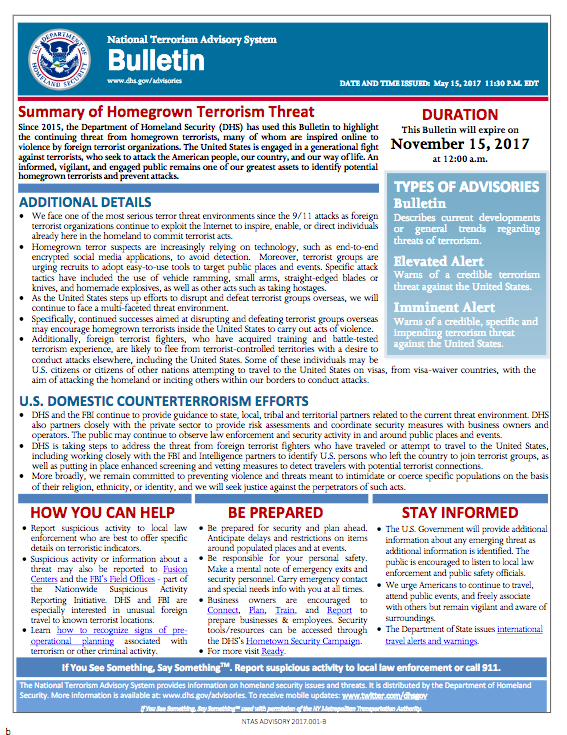

But, wait, an ongoing global cyberattack impacting critical infrastructure that has already caused disruptions that have led to physical impacts (such as the UK’s NHS having to delay patient treatment) and with the potential for impacts to critical lifeline infrastructure in the US, and from DHS we have… a statement? Well, as I drafted this post, DHS released a new National Terrorism Advisory System (NTAS) Bulletin – and we’ll return to that in a moment.

President Bush implemented the Homeland Security Advisory System (HSAS) in March 2002. It had its positives and its challenges and, after review, in 2011 the Obama Administration scrapped HSAS for the current NTAS (more background here). According to DHS, it “has never issued an Alert because neither the circumstances nor threat streams have risen to the required level or purpose of the system.” From the standpoint of a terrorism threat, on

President Bush implemented the Homeland Security Advisory System (HSAS) in March 2002. It had its positives and its challenges and, after review, in 2011 the Obama Administration scrapped HSAS for the current NTAS (more background here). According to DHS, it “has never issued an Alert because neither the circumstances nor threat streams have risen to the required level or purpose of the system.” From the standpoint of a terrorism threat, on e could argue whether an alert has been necessary at any time over the last five years or not (if we’re wanting to ban laptops on planes from half the world, maybe there’s a general or elevated threat…?). However, given the explicit focus on terrorism, NTAS isn’t really an applicable means to address the ongoing cyber threat anyway, as evidenced in the 15 May Bulletin. A generally useless statement that 1) drives no action whatsoever, and 2) cannot, by its focus, address an ongoing cyberattack impacting critical infrastructure.

e could argue whether an alert has been necessary at any time over the last five years or not (if we’re wanting to ban laptops on planes from half the world, maybe there’s a general or elevated threat…?). However, given the explicit focus on terrorism, NTAS isn’t really an applicable means to address the ongoing cyber threat anyway, as evidenced in the 15 May Bulletin. A generally useless statement that 1) drives no action whatsoever, and 2) cannot, by its focus, address an ongoing cyberattack impacting critical infrastructure.

So, what to do, what to do? How does DHS publicly notify the population of a threat concern and associated risks in an understandable, useful, predictable, repeatable manner in support of its mission and core capabilities such as Intelligence and Information Sharing, Cybersecurity, and Operational Communications? NTAS doesn’t usefully assist in communicating non-terrorism threats such as cyber and health threats (say, an emerging pandemic concern) and it is arguable if it provides any utility with regards to terrorism (the new Bulletin speaks to concerns regarding encryption but nothing at all over the items associated with the newly implemented and anticipated electronic device travel restrictions).

The 15 May NTAS update was a sort-of necessity; the previous one was set to expire and, absent a change of approach, the new leadership is continuing the process that is already in place. Secretary Kelly is executing the way many military leaders (and others!) do in transition – preparing to implement his stamp on the organization but, as he does so, “all existing plans and procedures remain in effect.”

The 15 May NTAS update was a sort-of necessity; the previous one was set to expire and, absent a change of approach, the new leadership is continuing the process that is already in place. Secretary Kelly is executing the way many military leaders (and others!) do in transition – preparing to implement his stamp on the organization but, as he does so, “all existing plans and procedures remain in effect.”

As the Trump Administration and new DHS leadership settle in, the conditions and processes by which threat and risk communications and associated recommendations are shared with the public need to be revisited with a more functional process implemented.

A follow-on to this post will suggest one way that this broad process may be refined.

Post Script: What recently got me thinking on this topic was an interview I had the chance to do with Bridget Johnson at PJ Media. In that interview, Bridget asked, “Six years ago, the U.S. government ditched the color-coded terror alert system for a National Terrorism Advisory System. Do entities feel more or less confused about the current state of alert under the colorless system?” To which I responded: “I love this topic! When I was supporting DHS we had numerous discussions revolving around HSAS and the colors and caveats. The need to improve that system was clear. But NTAS has been a fumble. Its not that its more confusing, its that its useless. It took a long time to try and apply it and when it was introduced, in some ways it ran counter to the way it was intended. Neither specific or really time-constrained, it isn’t telling anyone anything nor driving anyone to respond in any way. For the public, its useless. Run a poll and see how many people even recognize the term ‘NTAS.’ When you assess an exercise or real incident response, planning and communications almost always come up as areas that can be improved. With our threat levels, we need to develop ways to communicate threats clearly and effectively. Sadly, it becomes a political game and a bit of cover your bottom – no one wants to reduce a threat level and then have an attack the next day. The Bush administration sort of took on a ‘never again’ attitude after 9/11 and Obama didn’t do much to change that. That doesn’t help the public mentally prepare for the reality that terrorism will occur. But people get it. We’ve sadly had a number of incidents that have shown that – while absolutely tragic and devastating for the victims and their communities – the rest of America – and the many other nations that have been hit much harder – we go on. We mourn, but we’re not going to let some deranged extremists frustrate our way of life. We’re resilient. Our communications on threats should respect that, and leaders should be brave enough to accept they may get it wrong sometimes, because bad things happen.“

Gate 15 provides intelligence and threat information to inform routine situational awareness, preparedness planning, and to penetrate the decision-making cycle to help inform time-sensitive decisions effecting operations, security, and resources. We provide clients with routine cyber and physical security products tailored to the individual client’s interests. Such products include relevant analysis, assessments, and mitigation strategies on a variety of topics.

This blog was written by Andy Jabbour, Gate 15’s Co-Founder and Managing Director. Andy leads Gate 15’s risk management and critical infrastructure operations with focus on Information Sharing, Threat Analysis, Operational Support & Preparedness Activities (Planning, Training & Exercise). Andy has years of experience working with partners across the critical infrastructure and homeland security enterprise to support national security and client business needs.